AND THE WINNER IS:

JACOB ROSS FOR THE BONE READERS

On Friday 17th March, the winner of the inaugural Jhalak Prize for books written by British BAME authors was announced from a shortlist of six. Fiction and non-fiction, books for adults and books for children: all have been represented on the shortlist and I can’t begin to imagine how the judges are going to pick the final winner.

I’ve spent the last couple of months reading all the books on the Jhalak short and long lists and reviewing them for Book Muse UK. It has been an absolute joy - every one of the books a voyage of discovery. You can read extracts from my reviews below but first, here are some comments from four of the panel of judges: chair of the judging panel, Sunny Singh and her colleagues Musa Okwanga, Yvvette Edwards and Catherine Johnson.

Why were you keen to support the inaugural Jhalak Prize?

Sunny Singh: I founded the Jhalak Prize because I was tired of seeing brilliant writing not receive the attention it deserves, from the press, bookstores, prizes and therefore never getting to readers. And of course I was seeing great writing either not being published or not being published properly. I have been thinking about the prize for about four years now but after the Writing the Future report and various other attempts at raising the issues, we decided go ahead with it. I was at the Polari Prize and got talking to the judges and supporters and realised that a prize may push the issue into consciousness for the various players in the industry. Of course, I am also being selfish: I want to read the writing I love from writers I love. And hopefully Jhalak can help bring them into the market.

Catherine Johnson: The prize came out of BareLit, an incredible crowdfunded festival - I have been a published writer for over twenty years, and it has always been said, if not openly then tacitly that there is not the big audience for books written by BAME authors. This was the first time it was made blatantly clear that there really was a readership and an audience hungry for those stories.

Also, sadly, the 'big' awards in my field - eg The Carnegie, consistently ignore BAME writers - only two have ever been shortlisted in its 80 year history. Here is a chance to give those books air and space and the accolades they deserve. If the mainstream ignore us, why not do it ourselves?

Musa Okwanga: I feel that it is vital that writing of the highest quality gets its due recognition, whoever makes it; and that, so far, too many people of colour do not have the platform that their talents deserve. The Jhalak Prize, in my view, is a wonderfully proactive and progressive way to address that concern.

Just as the Baileys Prize (formerly the Orange Prize) did initially, any literary prize that restricts it potential entrants to a given category of writers tends to attract criticism that entrants are being judged not for their writing but by their gender/colour of skin etc. How do you answer that criticism in the case of the Jhalak Prize?

Sunny Singh: I don't and I won't answer this question! We know the playing field is not level. We have the statistics, the reports, the endless reams of paper but when we flag up the iniquities we are told to 'quit whining and do something.' Well, the Jhalak Prize is us DOING something. You don't like the Jhalak Prize? Then start with working to make that playing field level and actually based on meritocracy!

Catherine Johnson: I think the Bailey's Prize is a good parallel, it may have been contentious at the start but readers understand and accept it as a useful award which draws attention to the best of women's writing. Of course it would be brilliant if we didn't need a prize like this and there was that level playing field we've heard so much about. But there isn't. Society has its flaws. We could either lie down and accept that books by BAME authors are going to be overlooked or do something to draw attention to the fantastic breadth and depth of writing out there.

Musa Okwanga: I would say that this form of criticism of the Jhalak Prize is a little like criticising a doctor for diagnosing and providing medicine for an ailment, rather than criticising the causes of the ailment itself. Because I think that the lack of diversity in publishing at the moment is an ailment, and one which is depriving us all of some of the most exciting writing out there. So let’s do what we can to cure that.

Yvvette Edwards: There are many literary prizes. There are prizes that restrict submissions to writers from a particular part of the country, ones that only judge debuts or second novels or crime or romance or science fiction, or writers of a particular age or religion or gender, or any of a hundred other criteria. It is not a matter of discrimination why this is so, but an effort to ensure that writers who are unlikely to be put forward to or nominated for the big literary prizes, yet are nonetheless producing great writing - sometimes very progressive, experimental and original writing that deserves a wider audience - that those writers are acknowledged and the quality of their work is recognised. In the case of the Jhalak Prize, there’s nothing ominous about it; it’s simply another literary prize with a submission criterion.

It must be particularly challenging to judge a prize that encompasses non-fiction, adult fiction and young adult fiction and fiction for children. How have you approached making those sorts of comparisons?

Sunny Singh: As chair of judging panel, my role has been mostly to hear out what the panel has says. I think we were clear that books were judged within the category they fell. So YA was seen as amazing within that particular category. Nonfiction the same. And the rest. We got particularly lucky as so many of the books also transcended their particular tag. The shortlist is utterly extraordinary.

Catherine Johnson: I think this is one of the strengths of the prize. Isn't it marvellous to say Children's and YA are just as important as non fiction and literary fiction? Our prize is about readers just as much as writers, about saying to readers how wonderful and rich and varied the work that BAME writers are producing.

Musa Okwanga: The only true challenges have been the creation of a longlist, and then a shortlist - to say nothing of selecting the eventual winner. When judging work, I think that we have all tried to look for originality, for creativity - it will sound like cliche, but we have looked for work which has a unique voice. It’s been very difficult to narrow the submissions down, but I am confident that we have managed that.

Yvvette Edwards: The task was made much easier by the fact that we were not required to longlist a specific number of books. The decision was made early on that every book that deserved to be on the longlist would be, which meant that we were able to put forward every book that the judging panel agreed deserved to be nominated, irrespective of whether it was non-fiction or adult, children or YA fiction. Once we were down to the longlist, we had lengthy discussions about the merits of each book, judging them on their own terms and within their genre.

Can you tell us what has particularly excited you about any of the six books on the shortlist?

Sunny Singh: Gosh all of them! Insightful, innovative. One of the judges commented at a meeting that the longlist was made up of great books and the shortlist is all phenomenal ones. It's been a pleasure to read and reread them during the judging process. And one can't say that about many books, forget about all on a shortlist!

Catherine Johnson: Definitely the breadth and depth. Look at those books, every one is a total gem. I have no idea which is the winner, they all deserve the prize.

Musa Okwanga: We all have our own favourites, I am sure, but I have loved the bravery of the work - the fearlessness and empathy shown in tackling the most taboo of subjects. That’s all I feel that I can say publicly, but I will have to drop that particular writer a private message of congratulation at some point.

Yvvette Edwards: I have to say - and I am not attempting to be diplomatic or coy - that all the shortlisted books excite me. Every one of those books deserved its place on the Jhalak Prize shortlist and to be widely read. Although I had a couple of favourites in mind, I approached the final judging panel with an open mind, because any of those books would have been a worthy winner of the inaugural prize.

Finally, what are your hopes for the future of the Jhalak Prize?

Sunny Singh: I started the prize with the hopes of ending it! The prize succeeds when it is no longer needed. So that is all I hope for: that one day, in not too far future, a prize like the Jhalak Prize will not be necessary because it will truly be a 'level playing field.' I guess one can and must dream!

Catherine Johnson: I think the prize has hit the ground running, I hope it will grow and earn a reputation for flagging up brilliance across genres.

Musa Okwanga: That it will continue to flourish and to provide a platform for spectacular writing for as long as it is needed. It has been a pleasure, an honour and a privilege to have helped it on its way.

Yvvette Edwards: I hope it becomes an established fixture in the literary calendar, and that it goes from strength to strength.

Thank you! Look out for the announcement of the winner on the evening of Friday 17th March 2017.

Now here are my reviews of the six shortlisted books.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge

A day chosen at random - unremarkable in any way, including for the number of young people to die of gunshot wounds in a 24 hour period. On this day, seven of those killed were black, two Hispanic and one white. The oldest was nineteen; the youngest nine. “The truth is it’s happening every day, only most do not see it.”Each chapter is both a personal account of a young person whose life and death would otherwise have passed unremarked by anyone outside their immediate neighbourhood, and an essay on the factors that create this appalling death rate.

Segregation also creates a numbing distance across which empathy becomes all-but impossible. This book may be one strut in a bridge across that divide.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Read my full review here.

Speak Gigantular by Irenosen Okojie

Following on from her Betty Trask winning debut novel, Butterfly Fish, Speak Gigantular is Irenosen Okojie’s first collection of short stories. And it is almost certainly not like any other short story collection you have ever read. Okojie’s writing rarely stays long in the recognisable world of the five senses. In these stories, emotions take on physical form.These are unsettling stories. Reading them is like walking through one of those trick rooms whose crooked walls make you think the floor is unstable. Okojie’s range is formidable and her imagination extraordinary.

Genre: Short Stories

Read my full review here.

The Bone Readers by Jacob Ross

Two cold cases twist and turn through the pages of The Bone Readers. Michael ‘Digger’ Digson needs to find the truth behind the death of his mother, killed when he was a young boy. And his boss, Detective Superintendent Chilman, is obsessed with the case of Nathan, a young man who disappeared and whose mother is convinced he was murdered.Written by Granadan born Jacob Ross, The Bone Readers is set on a tiny, fictional Caribbean island. The multiple strands of the book all play on themes of sexual violence, sexual exploitation, gender power struggles and corruption. The women in the book are tough, shrewd, emotionally intelligent and sassy. Yet they are trapped by male prejudice, male violence and the male stranglehold on power. Many carry scars from the sexual violence they have experienced.

An unconventional crime novel, and one that exposes the dark underbelly of ‘paradise.’

Genre: Crime Fiction

Read my full review here.

The Girl of Ink and Stars by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Ink and stars - the two most fundamental tools of the cartographer.Isa is the daughter of a cartographer, and his unofficial apprentice. But Isa’s Da no longer roams the world to map its continents, but walks heavily supported by a stick. And the only guide to the Forbidden Forest is an ancient cloth map left behind by Isa’s mother. So when a girl is found dead in the Governor’s orchard, and his daughter, Isa’s friend Lupe, disappears into the forest, it is up to Isa to don the mantle of cartographer and guide the search party into the heart of the island, where no one has travelled for years.

Maps have a magic about them. They can say as much about the people who made them as they do about the lands they depict. Kiran Millwood Hargrave has spun that magic into a tale of adventure that is - as all good heroic journeys should be - about friendship and courage, self discovery and self sacrifice.

Genre: Fiction for 9-12 year olds.

Read my full review here.

Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga

Written as a companion to the BBC television series of the same name, David Olusoga’s book shows how the Black presence in Britain can be traced back to Roman times and has been a feature of life, particularly in London and other big cities, since Tudor times. It demonstrates how British economic interest, first in the slave trade itself and then in slave-produced cotton, warred for centuries with a mixture of the exalted believe that British air was ‘too pure for slaves to breathe’ and genuine courageous humanitarianism.Britain may have been one of the first countries to outlaw the slave trade, but in the years before abolition, it was also its biggest player. As Olusoga shows, British involvement in the slave trade began in the early 17th C and gained the Royal seal of approval in 1672. In just the 20 years before the slave trade was outlawed by Act of Parliament in 1807, three quarters of a million slaves were transported from Africa to the Americas aboard British ships.

Britain has things to be proud of in the history of relations with its Black citizens, but much to be ashamed of too. A powerful, emotional and eye-opening read.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Read my full review here.

A Rising Man by Abir Mukherjee

Calcutta in 1919.The “Quit India” movement is beginning to gain momentum. Calls for violent uprising clash with Gandhi’s approach of non-violent noncooperation. And the British were doubling down on their control with an oppressive set of laws called the Rowlatt Acts. In the midst of this, a senior British civil servant is found murdered in the ‘wrong’ part of town, with piece of paper stuffed in his mouth inscribed with a subversive slogan.Mukherjee takes you down into the streets of Calcutta, from the stinking gullees of Black Town and the opium dens of Tiretta Bazaar, to the poky guesthouses for the itinerant British, where “the mores of Bengal were exported to the heat of Bengal,” the maroon-painted colonial neo-classic buildings of the Imperial civil service and the exclusive clubs of the rich, mini Blenheim Palaces, sporting signs that declare ‘No dogs or Indians beyond this point.’

Genre: Crime Fiction, Historical Fiction

Read my full review here.

And my own personal favourite? One that only made it to the longlist, the haunting novel Augustown by Kei Miller.

Augustown by Kei Miller

Augustown is a poor suburb of Kingston, Jamaica, set up by the slaves set free by royal decree on 1st August 1838. It is also closely associated with Alexander Bedward, the preacher who inspired Bedwardism, the roots from which grew Rastafarianism.Kei Miller’s novel takes place largely in 1982, when most of those who remember Bedward are dead or dying and the events of his life have become tales told by grandmothers like Ma Taffy. And on the day that Ma Taffy sits up straight on her verandah and smells something high and ripe in the air, she knows an autoclapse is coming. ( Autoclapse: (Noun) Jamaican Dialect. An impending disaster; Calamity; Trouble on top of trouble.)

A stunning novel that takes modern Jamaican history (and the history of Rastafarianism in particular) and spins from it a fable the might stand for any people suffering from ingrained economic disadvantage and religious intolerance.

Genre: Literary Fiction

Read my full review here.

Finally, a couple of 'special mentions' from Yvvette Edwards of books that did not make the longlist:

"One of the books that excited me was Hibo Wardere’s incredibly brave memoir, Cut: One Woman’s fight against FGM in Britain Today, which was a harrowing yet life-affirming read. Another personal favourite of mine was a children’s book, The No1 Car Spotter Fights the Factory, by Atinuke. Aimed at 6 to 9 year olds, it was a social commentary on the positive power of social media and the capacity of the community to affect change, whilst exploring the reality of the lives of the poor in third world countries and the ways in which they are exploited by large corporations. At the same time, it was a genuinely enjoyable and accessible read."

-and-the-cast-of-Harry-Potter-and-the-Cursed-Child--Photo-by-Manuel-Harlan_qwpym4hx3v6dp6z57xonuv.jpg)

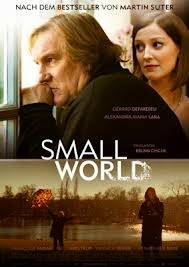

A moving and unusual book, which tells the story of Konrad, now in his 60s, who has enjoyed a long association with the Koch family of Zürich. He’s getting forgetful, and the family suspect him of drinking a little too much for his own good. When his absent-mindedness leads to a fire which destroys their villa, something has to change. Gradually it emerges that Konrad is suffering from Alzheimer’s, and as his grip on the present loosens, he recalls more and more about the past. Something Elvira Koch, the family matriarch, fears the most. Swiss author Suter draws his characters with balance and depth, and uses the gentle, but inexorable pace of the story to increase the tension, pile on the pressure and offer poignant insights as to the nature of the disease, of memory and the dangers of secrets.

A moving and unusual book, which tells the story of Konrad, now in his 60s, who has enjoyed a long association with the Koch family of Zürich. He’s getting forgetful, and the family suspect him of drinking a little too much for his own good. When his absent-mindedness leads to a fire which destroys their villa, something has to change. Gradually it emerges that Konrad is suffering from Alzheimer’s, and as his grip on the present loosens, he recalls more and more about the past. Something Elvira Koch, the family matriarch, fears the most. Swiss author Suter draws his characters with balance and depth, and uses the gentle, but inexorable pace of the story to increase the tension, pile on the pressure and offer poignant insights as to the nature of the disease, of memory and the dangers of secrets.